Today, the meaning and origins of the Seal of Suleman, a six-rayed star, have largely faded, particularly in the modern Muslim world. Morocco is the only Muslim state which still features the Seal of Suleman on its flag today. However, it uses the pentagram, rather than the hexagram, adopted by King Yusuf in 1915.

The David Star today is recognised as a Jewish symbol, associated to the Zionist movement, and featuring on the flag of the State of Israel, perhaps the most infamous case of modern colonization. However, historians have contested the Star of David's status as a true Jewish symbol, arguing that it lacks the necessary characteristics and origin of a genuine symbol, emphasizing its roots in the Muslim tradition.

The deployment of the David Star as a symbol of hate and oppression by the apartheid state of Israel against Palestinians is dangerous, given its historical significance, for it is an appropriation of history. It is also particularly painful for Muslims, witnessing a symbol they once revered as sacred being seared into their skin, and burned into the very Earth of their land. Neither of these is limited to the Middle East: the David Star was used to desecrate a cemetery in Germany, illustrating the international scope of hate, and support for the ongoing Palestinian genocide.

So, what is the Seal of Suleman? Long ago, when Prophet Suleman (A) was granted the power to command men, animals and Jinns alike, he possessed a ring with which he upheld his kingship and did as Allah willed.

It is written in the Holy Quran, Chapter al-Naml: 17: “And gathered for Solomon were his soldiers of the Jinn and men and birds, and they were in rows”.

One night, Hazrat Suleman (A) entrusted his ring to his favorite wife, Jarada. A demon, reffered to as Asir in some sources, and Sakhr in other accounts, assuming the guise of the Prophet, tricked her into handing over the ring. When Hazrat Suleman (A) returned, Jarada accused him of being an importer. By the time they understood what had happened, the demon had seized Hazrat Suleman’s throne, and was ruling in the Prophet’s stead.

Another verse in the Quran, Chapter Sad: 34 reads: “And we certainly tried Solomon and placed on his throne a body; then he returned”.

Sakhr tossed the ring into the sea, hoping to banish Hazrat Suleman (A) for ever. Wandering as a common man, Suleman (A) befriended a humble fisherman. Fate smiled upon him when the fisherman caught some catch, and cut up the fish to discover a ring inside it. It was the Prophet Suleman's ring! Reunited with his source of power, Suleman (A) reclaimed his kingdom.

As for what it appeared to look like, the secret has been lost to the echoes of time. However, in all likelihood, Hazrat Suleman’s ring included an engraved seal, as was the tradition at the time for Kings and statesmen from the sun-kissed realms of Egypt to the majestic courts of Persia and Babylon.

It was not until the 9th century that a hexagram or pentagram was used as the ring's definitive shape, in a religious context, by medieval Muslim writers and illustrators. Despite this representation, scholars continued to suggest alternative possibilities, such as the Shahada as a plausible design of the seal.

Nomenclature and Associations: a timeline

Several Muslim writers wrote extant works, which mentioned the Seal, including the Sahabi, Ibn Abbas, and several later scholars, namely, Al Tabari, Ibn Abu Hatim and Al Suyuti.

Gershom Scholem revealed that the Arabs birthed the name "Seal of Suleman." Both, five and six-rayed starts, were used to represent the seal, with no distinction in Arab tradition in the early Middle Ages. E. Fernández Medina attested that old Christian communities, touched by Andalusian Muslims, also recognised the hexagram as the Seal of Solomon.

The symbol was not used in Jewish Kabbalistic traditions till the 12th-century. The Seal of Solomon's association with Judaism was confined to Kabbalistic grimoires in medieval Spain and Central Europe, where it served as a symbol in occult practices rather than carrying religious connotations.

The prevailing view among scholars is that the symbol found its way into the Kabbalistic tradition from Arabic literature. On the other hand, the depiction as a pentagram appears to have originated in Western Renaissance magic, which, in turn, drew significant influence from medieval Arab and Jewish occultism.

In the 14th century, King Charles IV of Bohemia assigned Jews in Prague a red flag bearing Solomon's Seal; after the Battle of Prague in 1648. A new flag with a yellow hexagram on red, featuring a star at its center, was granted to the Jews for their defense efforts, with a replica preserved in the Altneushul Synagogue.

A story of Hazrat Suleman (A) was adapted and included in the Kebra Nagast, The Glory of Kings, Ethoipia’s 14th- century counterpart of the Persian Shahnameh.

It was by the 16th century that the Seal of Suleman was gradually replaced by the Ottomon crescent and star as a popular symbol, with the hexagram being left to it’s associations with mysticism.

The hexagram, gained prominence as the Star of David in the 17th century, coined by Central and Eastern European Jewish communities, as the Seal of Solomon Magen David, with the name evolving from Magen David, David's Shield, and finally, to the Star of David.

The Seal was not associated to European occultism till the after the Renaissance, and a resurgence in various movements related to magic and paganism in the 18th-20th centuries.

From the 19th century, the hexagram transitioned into a symbol for Jews, initially associated with the Zionist movement and later adopted universally. Chosen for the 1897 First Zionist Congress, its emblem featured six stars and a lion at the center, designed by Lithuanian-Jewish businessman David Wolfsohn, though its use remained niche due to varying acceptance of the Zionist movement among Jews.

The Nazis employed it to identify and mark Jewish citizens in occupied areas, with the yellow hexagram badge introduced across all of occupied Europe from September 1941 onward, marking a tragic turn in its historical significance.

Elevated by the wartime suffering of the Jewish people and rooted in its 19th-century role as the symbol for the Zionist movement, the hexagram gained global recognition, coming to symbolize Judaism itself.

Following the establishment of Israel in 1948, this emblem was officially adopted on October 28, featuring prominently on the national flag between two parallel blue bands, a design directly influenced by the flag of the First Zionist Congress.

Visual Representation

From the soaring arches of Islamic architecture to the delicate pages of manuscripts, from ornate jewelry and homeware and to amulets guarding against the Jinns, a concept which was born out of Hazrat Suleman’s command over the supernatural, the Seal is an omnipresent emblem in Islamic culture.

A Baybar's Quran, penned entirely with gold for a Mamluk Sultan; A 16th-17th century manuscript from China; Other manuscripts

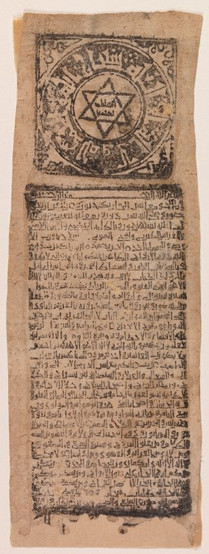

An 11th-century Talismanic scroll, block-printed on paper; A panel inlaid with the Seal of Hazrat Suleman (A) from the early 9th century. The carved vine leaves, scrolls, border designs, and other details of this panel are typical of early Islamic woodcarving.

Talismanic garments from Ottoman Turkey

Graves of the Ahl-e-Bayt, Jannat ul Baqi before demolition.

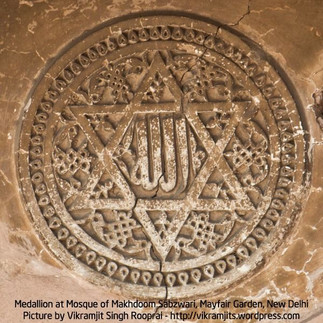

Humayun’s tomb, the Makhdoom Sabzwari Mosque in Delhi, the Muhammad Ali Pasha Mosque in Cairo

Uch Sharif, Pakistan; Tomb of Bahauddin Zakariya, Multan; the Seal of Suleman engraved on the floor at ruins near Gharo, Thatta

Seljuk-era gravestone; Ulu Camii, Turkey; Halil Ur-Rahman Mosque, Turkey; Pertevniyal Valide Sultan Mosque, Turkey

Qutb Complex, built by the Khandaan-e-Ghulamaan in the Indian Subcontinent.

A 5th-century blanket from Egypt; Batik cloth "besurek" from Jambi, 19th/early 20th century

Accessories from Libya: a necklace and a brooch

The flag of the Empire of Karaman. The Karamanids rose to power as the Seljuqs waned. King Hethum I accepted their Khan as sovereign, as they fought the Ilkhanids, closely allied with the Mamluks of Egypt. The town of Larende is now known as Karaman in honour of this very dynasty.

The flag of the Pirate-turned-Ottoman-Admiral, Hayreddin Barbarossa.

The second flag of the Alaouite Dynasty of Morocco, from 1795-1915.

In South East Asia, it was often drawn with loops. The 'Ring of Solomon' on two seals of Sultan Mandar Syah of Ternate, who ruled from 1648-1675.

Coins from Turkey

Seal of Emir Abdelkader Al-Djazairi the leader of the Algerian resistance (1832-1847) against the French occupation.

The history of symbols is not without nuances. Whilst understanding true meaning and origin remains crucial, It is important to remember that societies do not exist in isolation, and many modern symbols have roots in ancient, pre-Abrahamic civilizations from the Gandhara to Mesopotamia to Egypt.

The hexagram too, before being recognised as the Seal of Suleman upon its entry into Muslim fiction, has deep-rooted origins spanning across several ancient traditions of the East. It commonly appears in artefacts and architecture from the Gandharan civilization. In ancient Egypt, the hexagram, composed of six triangles, served as the hieroglyphic for the "Land of the Spirits," embodying the resurrection of the first man-god, Amsu.Its presence in ancient Armenia and Mesopotamia is evidenced by the oldest known depiction, dating back to the 3rd millennium BC, discovered in the Ashtarak burial mound in Armenia, from where it was passed on to the Babylonians. Tibetan Buddhism incorporates the hexagram with a Swastika inside in some versions of the Bardo Thodol, particularly associated with Vajrayogini. Additionally, it appears in Viking and Hindu symbolism, it signifies the duality of femininity and masculinity through the downward and upward triangles, respectively.

Gothic architecture, associated with Christianity, has its roots in Muslim European tradition, beautifully explained by Diana Darke in Stealing from the Saracens. Similarly, the art history of glass in the Islamic world has been inspired and influenced by the Roman Empire.

Comments